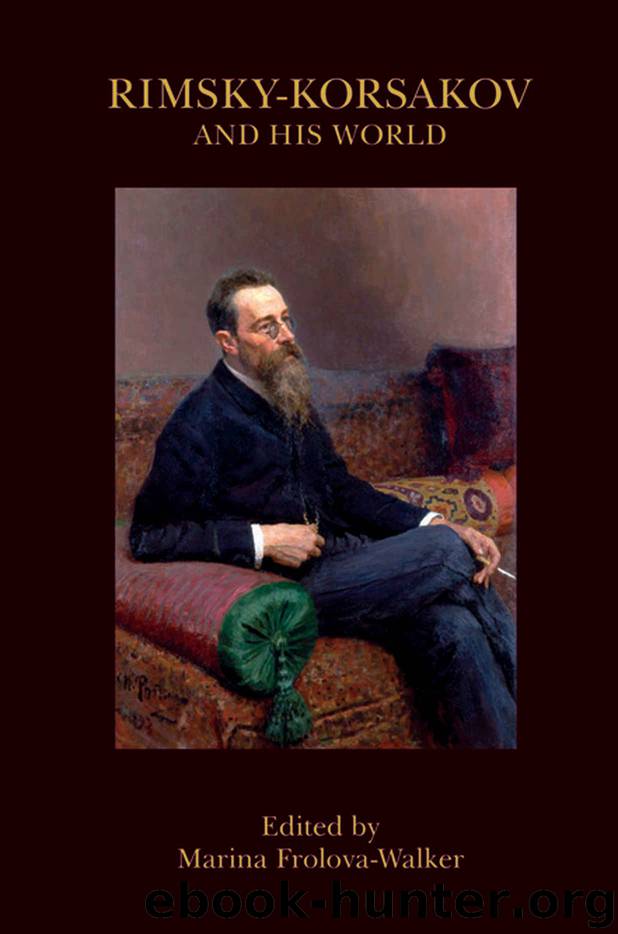

Rimsky-Korsakov and His World by Marina Frolova-Walker

Author:Marina Frolova-Walker

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2018-09-10T16:00:00+00:00

Figure 2. Sergei Zimin’s cockerel doodle.

In 1918, Adolph Bolm brought The Golden Cockerel to the Metropolitan Opera, prompting a sumptuously illustrated article in the New York Times. The reporter described the logistical nightmare of getting the opera to the United States from Russia before noting the opera’s “bitter irony toward a paternal government, savage satire as regards the Russian people.”25 The production was interpreted as a portrait of the decline of Imperial Russia in the run-up to the Revolution, specifically the 1905 uprising against the abuses of the last tsar, Nicholas II, and the entire clueless, snoozing aristocratic establishment. Obviously the Russian censors had hoped to prevent just that interpretation, but Rimsky-Korsakov’s publisher, P. Jurgenson, printed the music and libretto without the changes entered, allowing the uncensored version to be performed in subsequent years.

Yet what else might the work, in any form, be about? Is there space for interpretation beyond the politics of 1905? Three spheres emerge in the opera as in the ballet versions of The Golden Cockerel: the human, represented by Dodon (his name deriving, according to Belsky, from the Italian Dido, Didone,26 but perhaps also from the French words fais dodo, meaning “Go to sleep”) and his court; the fantastic, where the Astrologer dwells; and the erotic exotic, home to the Astrologer’s forever beloved Queen. The opera inverts Russian convention: the real Russian characters lose; the fake ones, the non-Russian characters from who knows where, win (or at least have the last word). The spheres overlap, but the composer seems most invested in the Queen and her domain. Rimsky-Korsakov began composing there, and the music of the middle act spreads outward, as if spun in a centrifuge, reaching both forward and back. The music does not progress in narrative form; rather it radiates, inward and outward. The music Dodon sings, and pantomimes, interacts with the whole-tone and octatonic music of the Astrologer (when Dodon realizes, at rehearsal number 98 of Act 2, that his dreams of the queen might be coming true), which interacts in turn with the semitone-and-augmented-second-laden music of the Queen. She reigns supreme, exerting power over the Astrologer, who exerts power over Dodon.

Richard Taruskin, a strong advocate for and defender of Rimsky-Korsakov’s fifteen operas, has called The Golden Cockerel a “trifling parody” compared to the others.27 Marina Frolova-Walker, however, describes the score as a kind of swan song to all that had defined Russianness in music as prescribed by the Kuchka—especially considering that if Rimsky-Korsakov had been interested in setting authentic urban and rural (popular) songs, as opposed to lampooning them, he could have consulted the recordings made by the ethnomusicologist Yevgeniya Linyova.28 Both Taruskin and Frolova-Walker point out that Rimsky-Korsakov knew these phonographs, but obviously did not find them useful. Instead, the composer clearly enjoyed abusing the Russian nationalist music of his own past, presenting folk fare in The Golden Cockerel in caustic travesty. In Frolova-Walker’s telling: “The goal of unifying the nation through music was now gone: there would be no more Ruslans or Prince Igors.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Actors & Entertainers | Artists, Architects & Photographers |

| Authors | Composers & Musicians |

| Dancers | Movie Directors |

| Television Performers | Theatre |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31959)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31945)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26607)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19053)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17417)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16050)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14174)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14081)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13341)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12403)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9004)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8930)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7673)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7587)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7352)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6210)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5455)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5385)